La convivencia

A period of idyllic religious tolerance and cultural flourishing? A marketing myth to sell the romantic landscape of Andalucía? Something else entirely?

If you have ever traveled to southern Spain and taken a tour of almost any major city—Córdoba, Málaga, Sevilla, Granada—you have probably heard the term convivencia. Related to the word vivir, to live, it means coexistence or co-living and refers to the period between 711-1492 C.E. when Jews, Christians, and Muslims all inhabited the Iberian Peninsula. In a lot of tourism materials this period is represented as a kind of idyllic past in which there was a peaceful and respectful attitude between cultures and religions. I have even heard it described once, incredibly by a professor, as a time when Christians, Muslims, and Jews could “sit down and have a cup of coffee together.” The image that the comment was intended to convey of the relationships between the religious groups is problematic in a multitude of ways, not the least of which in that it pretends that the Jews, Christians, and Muslims of the convivencia were monolithic groups that always got along and that the only possible tensions could be inter-religious as opposed to inner-religious. It also seeks to characterize 700+ years of history—politics, religion, warfare, art, and trade—with a single, pithy little image of conviviality and peace.

The Alhambra, a palace and military fortress built between the 13th-15th centuries by the Nasrids who ruled the Emirate of Granada, and one of the most enduring visual symbols of the convivencia.

To begin what will be a series of pinchos de cultura exploring various aspects of the convivencia, let's first get a sense of who the main players were at the outset of the period.

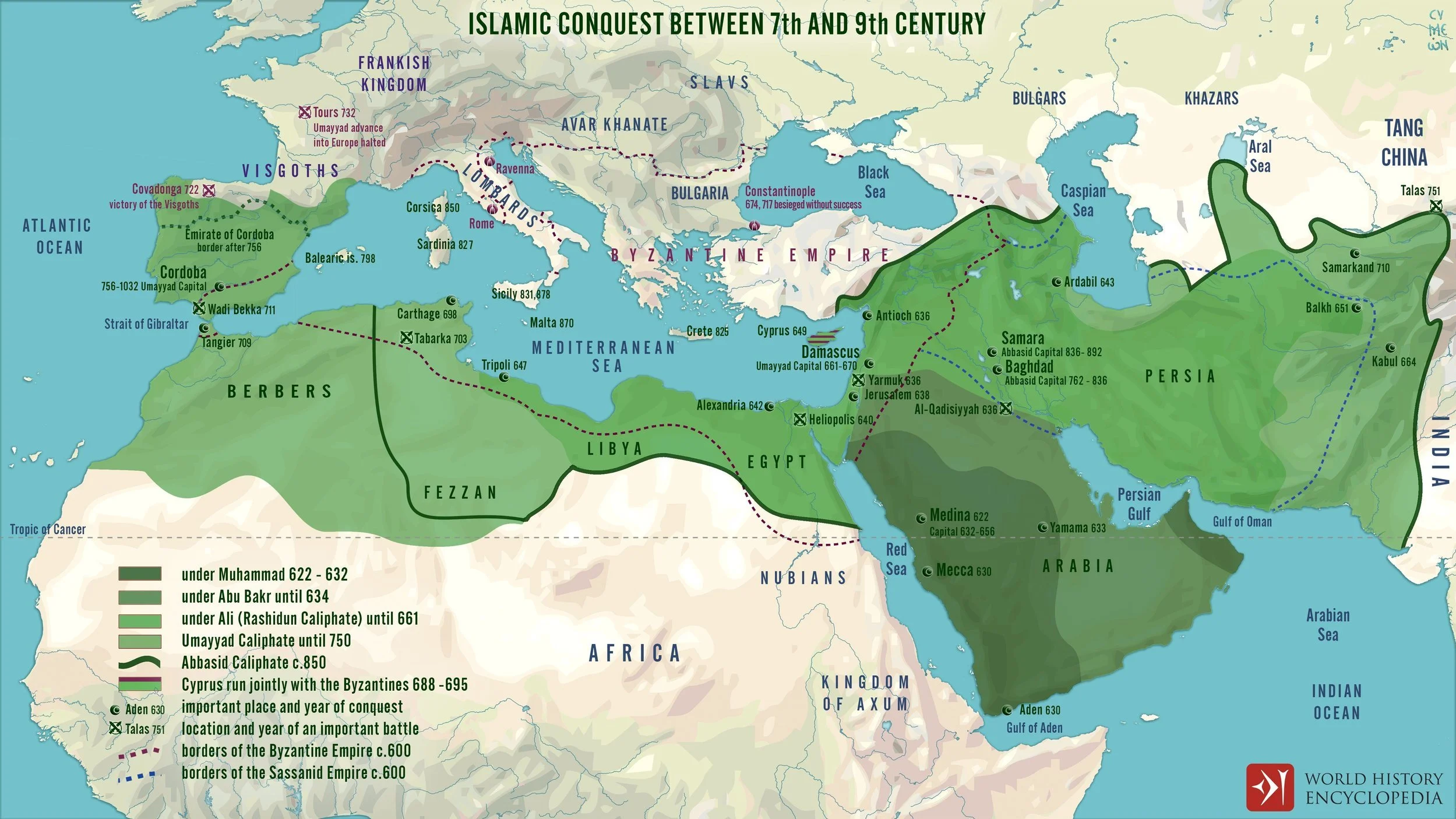

In 711 C.E., when Muslims first invaded and colonized the Iberian Peninsula, they were certainly united by their religion, but not by their ethnicity, a fact that caused various political problems within the newly conquered territory, which they called al-Andalus. The majority of the invaders were Berber Muslims from North Africa, relatively recent converts to Islam themselves, as Islam was only about 100 years old at the time and Muslim armies did not move into the area known as the Magreb until 661 C.E. Along with these Berber Muslims were Arab Muslims who led the offensive and who were ultimately responsible to the Umayyad caliphate in Damascus. Following the conquest, as the land was divided as reward amongst the invading forces, Arab Muslims routinely received the best tracks of land, leaving their Berber counterparts with less desirable allotments and a roiling sense of resentment. This resentment nurtured political instability in the early days of Muslim rule in the peninsula, a situation that would not become more settled until the arrival, in 755 C.E., of one Abd al-Rahmann, the only survivor of the Umayyads from Damascus after their family had been slaughtered and the caliphate taken over by the Abbasids. Abd al-Rahmann’s mixed Arab and Berber heritage, as well as his royal parentage, placed him in an ideal position to take advantage of the political instability of al-Andalus and in 756 C.E. he launched a battle against the then-emir of Córdoba and won, becoming the ruler of the province.

Political instability was nothing new in the Iberian Peninsula, however, and it did not begin with the Muslim invasion. In fact, the Muslim invasion was perhaps so successful due to the unrest and political infighting amongst the Christian Visigoths who ruled the peninsula prior, even if they were not a majority. The majority of the peninsula’s inhabitants were Hispano-Romans who had lived there since it was conquered by Rome in the third century B.C.E. The peninsula was conquered again by the Visigoths in the early fifth century C.E., and thus began a new age of political control by a minority faction. The Visigoth rule was forever plagued by political instability due to its basis in elected kingship. The death of every monarch created a new round of political warfare amongst the nobility as they tried to determine who would become the new monarch, and it was just such a situation that the Muslim invaders were able to take advantage of when they entered the peninsula in 711 C.E. The death of the previous king, Witiza, was followed by the election of Rodrick, but there was also a faction who supported the late king’s wish that his son Akhila succeed him. In addition to these factors splitting the ruling class, there was also a cultural division between the ruling class of Visigoths and the majority under-class of Hispano-Romans that was ripe for exploitation.

While the rulers of the Iberian Peninsula during the time known as the convivencia were confessionally Christian or Muslim, Jews also played an important part in the cultural and political landscape. Present in the peninsula before either their Christian or Muslim neighbors, Jews in ancient and medieval Iberia lived under a variety of agreements with the ruling classes, at times in relative peace and holding positions of great prestige and power within Muslim and Christian governments, and at times the victims of accusations of blood libel and of having caused outbreaks of the plague. Their position was ever-tenuous.

This first pincho de cultura on the convivencia is intended only to provide a sketch of the main groups at the outset of the period, about which tomes have been written and which I cannot hope to adequately cover in these small little summative pieces. Future installments will cover later parts of the convivencia and also focus more on the cultural interactions and shared arts, literature, and architecture that were produced by this unique confluence of peoples. And while these few paragraphs have in no way plumbed the depths of the diverse stories that line these 700+ years of history, I hope they have convinced you that there is no way to really sum up the convivencia, no way to pin it down and define it. It is an anomaly, a site of intersections and contradictions, of flourishing and oppression, of peace and war, of admiration, appropriation, and acquisition.

A brief timeline of the events/ periods mentioned in this piece:

3rd century B.C.E.– Rome conquers the Iberian Peninsula

5th century C.E.– Visigoths conquer the Iberian Peninsula

661 C.E.– Muslim expansion into the Maghreb

711 C.E.– Muslim invasion of Iberian Peninsula

755 C.E.– Abd al-Rahmann arrives in Muslim Iberia, called al-Andalus

756 C.E.– Abd al-Rahmann becomes the ruler of the province after a brief battle with the emir backed by Damascus

1492– Isabel and Ferdinand, the Catholic Monarchs from Castilla and Aragón, conquer Granada and shortly thereafter expel the remaining Muslims and Jews from the peninsula

Sources consulted for this piece:

A Concise History of Spain, William D. Phillips Jr., Carla Rahn Phillips